Breaking Rust, AI Slop, and the Long War over Real Music

When innovation hits the charts, critics cry “not real”—but listeners tell a different story.

The song dropped a few weeks before Thanksgiving, and tastemakers attacked. They ranked it at the bottom, sneered that the artist wasn’t real, dismissed it as novelty, and excoriated the music for being just plain bad. Not serious. Not authentic. Not real.

Then it went to Number 1.

I’m not talking about recent and mysterious AI act Broken Rust’s number one country hit, “Walk my Walk.” I’m talking about Alvin and the Chipmunks.

In 1958, Ross Bagdasarian was a struggling actor and songwriter. He’d had an Alfred Hitchcock cameo and he co-wrote a hit for Rosemary Clooney, but the money had dried up. In fact, before that, he’d tried grape farming in the late 1940s and his crop literally dried up. When your resume includes “failed raisin magnate,” you’re not exactly on the glide path to stardom.

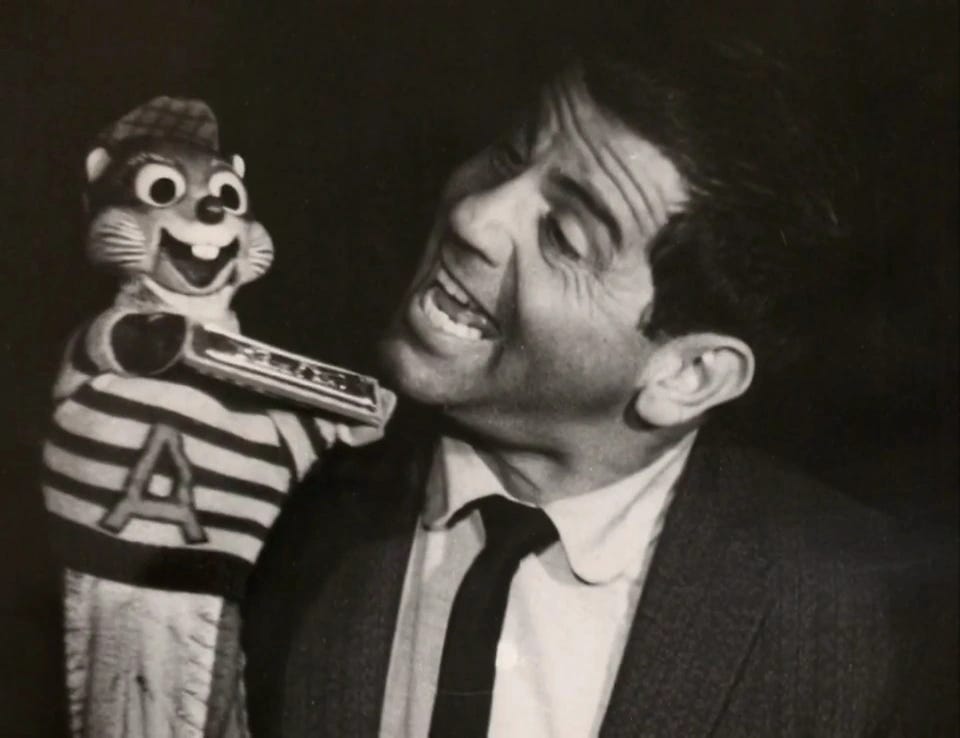

By this point, he had about $200 to his name, according to his kids, and spent $190 of it on a vari-speed tape machine. He discovered that if he sang very slowly into the recorder at half-speed, then played it back at regular speed, his voice turned into a helium-induced cartoon. Then he had an idea, a song about seeking advice from an alternative healer. He wrote and recorded “Witch Doctor” using the vocal trick.

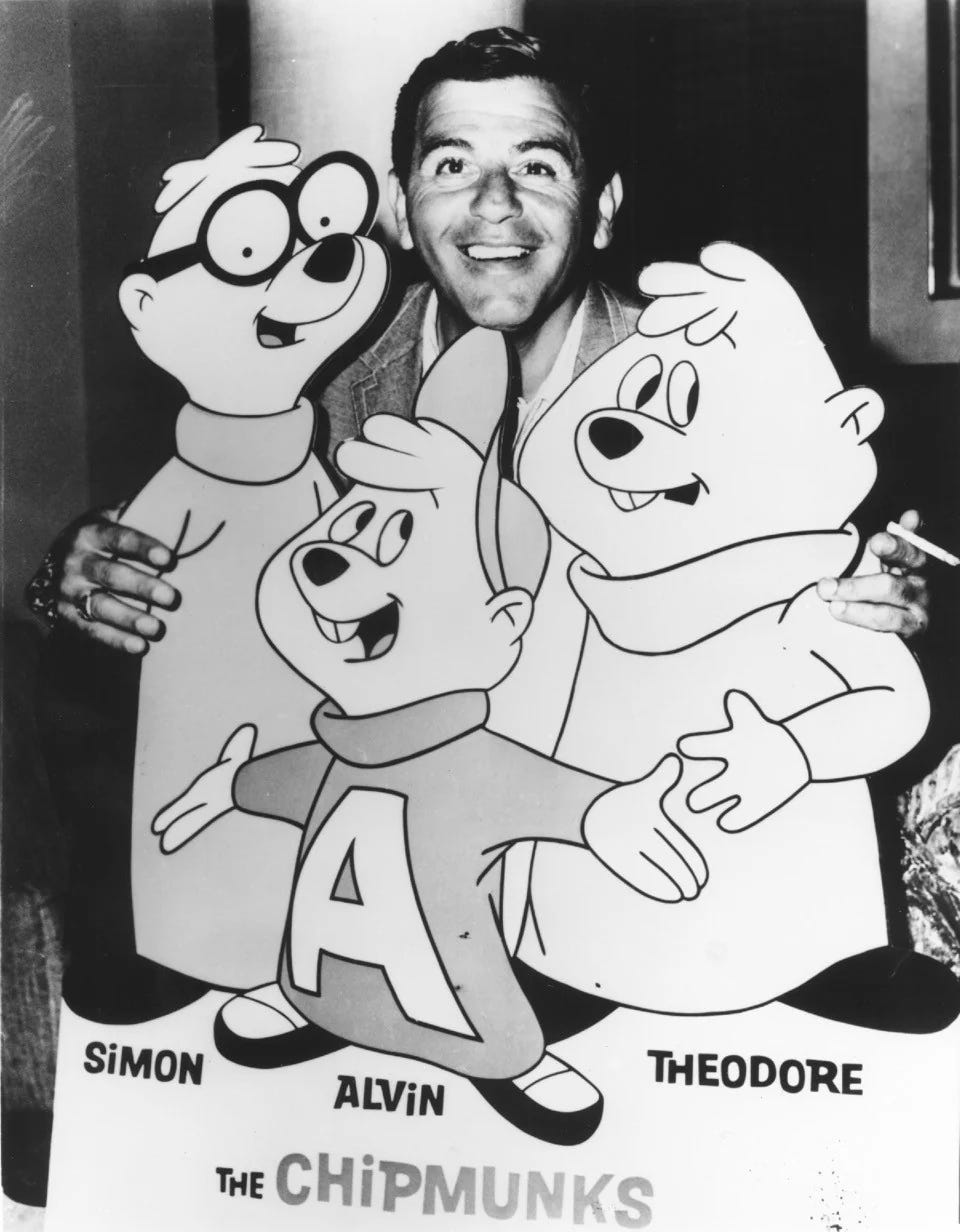

The executives of Liberty Records, Alvin Bennett, Simon Waronker, and Theodore Keep, were close to bankruptcy and bet it all on releasing this odd song. In April, 1958, “Witch Doctor” rocketed to the top of the charts.

Riding that success, months before Christmas, Bagdasarian’s four-year old son began the annual parental torture ritual, “When is Christmas?” That gave him another song idea. He whistled the tune into a tape recorder (he couldn’t play an instrument) and wrote a Christmas song. But he felt it shouldn’t be a choir, it should be singing insects or animals. He eventually landed on Chipmunks.

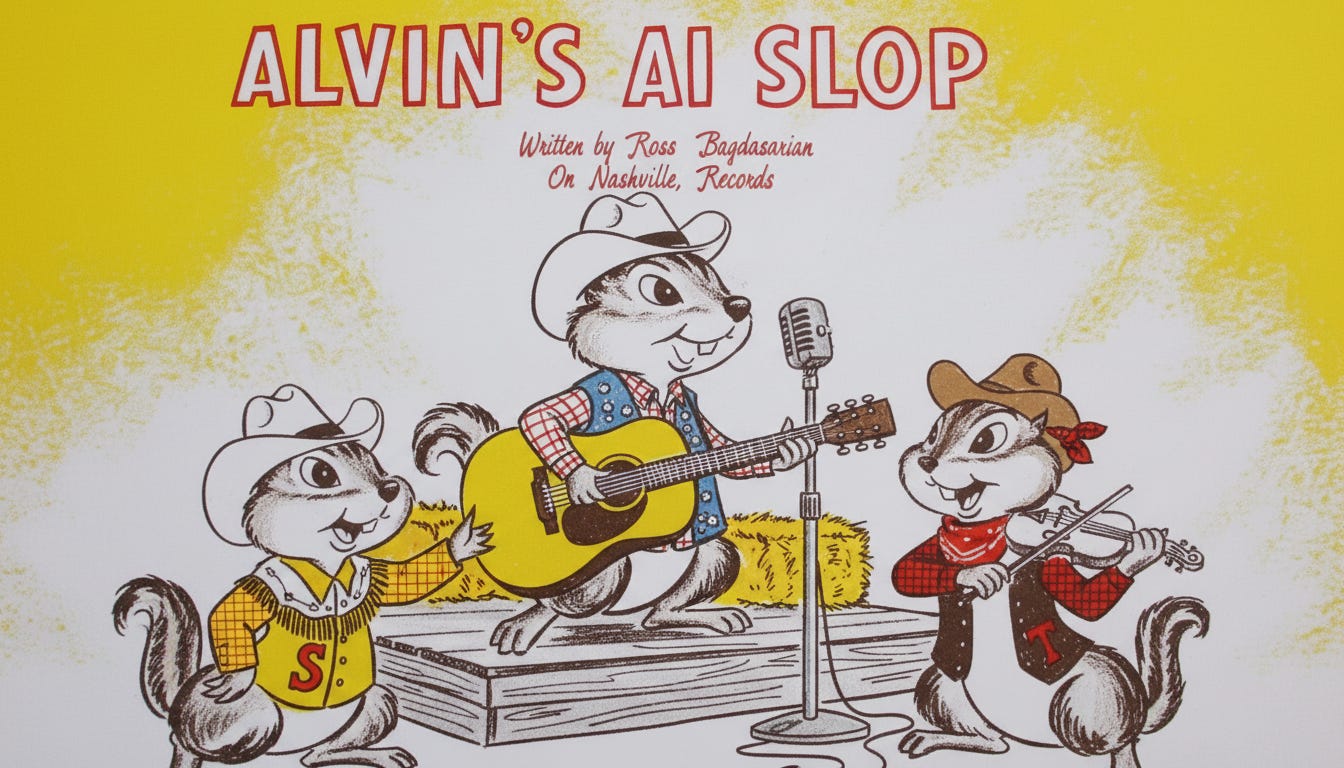

He took the stage name David Seville and named his high-pitch trio after those Liberty Records execs.

“The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late)” debuted on American Bandstand’s “Rate-A-Record” segment. It scored the lowest possible rating of 35 across the board. As bad as it gets. Critics called it novelty. Even decades later, writer Tom Breihan praised its ingenuity but also called it a parlor trick and added, “As a piece of music, it sucks shit.”

Listeners didn’t care.

The Chipmunks spent four weeks at Number 1, stayed on the charts for thirteen weeks, and was the last number one Christmas song until Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You” in 2019. The record also won three Grammys at the inaugural event.

None of this is surprising.

When artists use new technology to make new kinds of art, some gatekeepers respond by declaring it “not real.” A 15th century monk said the printing press made a “harlot” of literature. Music legends warned that synthesizers would “destroy souls.” Today, critics slap the label “AI slop” on AI-generated music and content. The charge is the same: that this isn’t real art because it lacks human experience and depth.

Maybe “The Chipmunk Song” really is a parlor trick. Maybe Broken Rust’s “Walk My Walk” really is “AI Slop.” But once something hits Number 1, we’re forced to face an uncomfortable question: if millions of people like it, what about it isn’t “real”?

That’s not to say that popularity settles an argument. Plenty of popular things are shallow and disposable. But popularity does tell us that something is happening in people’s heads and hearts. A recent Deezer-Ipsos survey found that 97% of listeners can’t tell the difference between AI and human-composed music. If most people can’t hear the difference, then “this isn’t real” can’t just be about how it sounds.

Often, the accusation is about jobs. Historically, when new tools arrive, critics pair their aesthetic complaints with concerns about “real” artists losing work. “AI slop” can work the same way. It’s a taste judgment but carries a quieter concern of what if this new stuff replaces us.

That fear isn’t fake, but dismissing the tech as fake or unworthy doesn’t solve the problem. It just insults the audience. If the concern is that algorithms and bots are juicing engagement, then the argument is not with the songs, it’s with the incentives and the business model. If the concern is that artists will lose their work, then the argument is with how we structure rights, revenue, and opportunities for human creators.

Ross Bagdasarian’s chipmunks remind us that listeners have always had a soft spot for gimmicks, novelties, and new sonic landscapes. And those experiments can become part of the canon, not by passing a purity test, but by connecting with people. As AI tools flood the landscape, artists must rethink their advantages that no model can automate. (On this, I just had a great conversation with Bandcamp’s Dan Melnick - more later.) And critics can retire the border-patrol badge and help us tease out why sounds land in the first place, and what that says about us, the humans.