Practice Didn’t Die, It Moved: Auto-Tune and Death Cab for Cutie

What Auto-Tune teaches us about adapting craft, culture, and practice

The indie rock band, Death Cab for Cutie, arrived at the 2009 Grammy awards in protest. With baby blue ribbons prominently pinned to their lapels, they decried a contaminant sweeping the globe. It poisoned natural beauty, concealed human error, and bulldozed diversity. Not oil. Not chemicals. Auto-Tune.

On the red carpet, they warned of a music industry awash in the “digital manipulation” of thousands of singers. But this admonition wasn’t new. It was another verse for the chorus that has echoed since the first vocoders crackled to life. It didn’t sound human, critics had charged; it scrubbed away the small imperfections that make performances feel alive and authentic.

Bassist Nick Harmer added that because of Auto-Tune, “musicians of tomorrow will never practice. They will never try to be good, because yeah, you can do it just on the computer.” We’ve heard this lyric before.

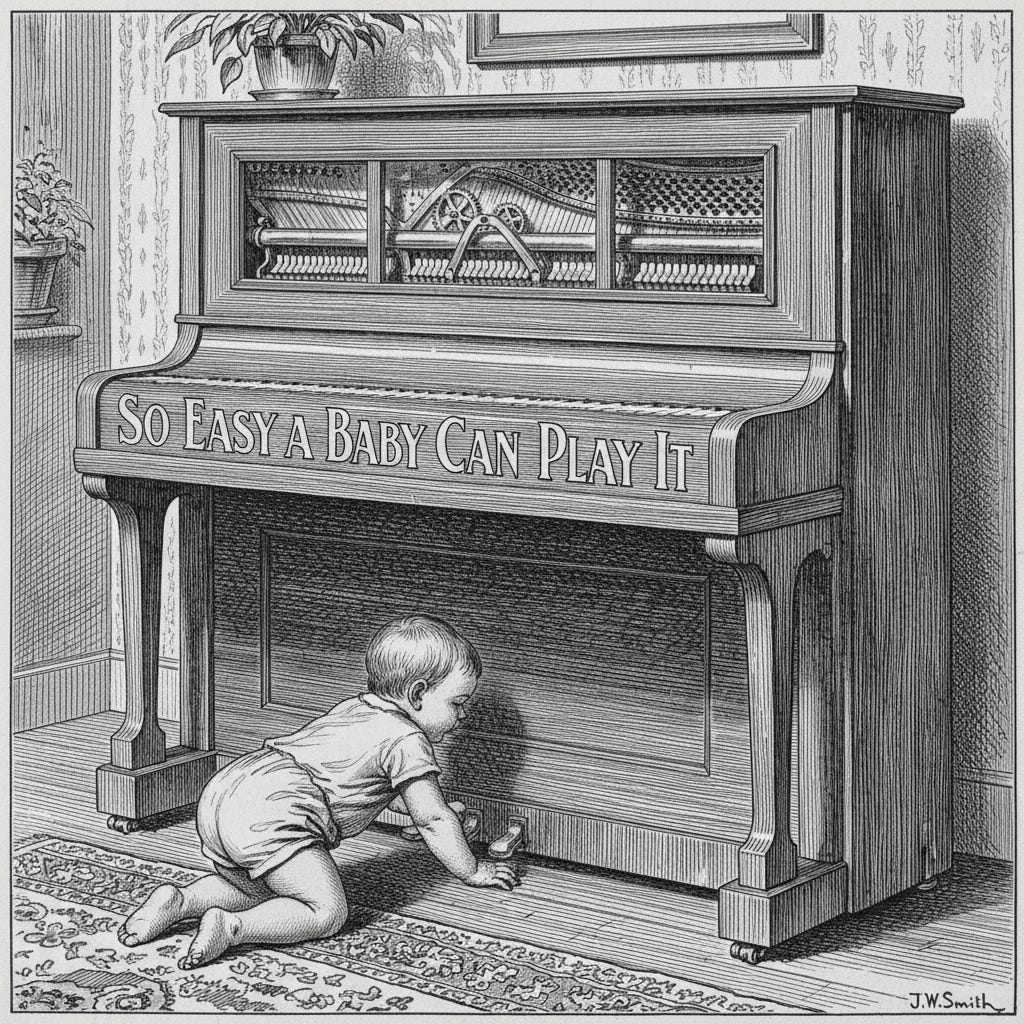

Another musician had similarly worried over a machine in music: “And what is the result? The child becomes indifferent to practice.” When music can be easily acquired, he continued, “without the labor of study and close application, and without the slow process of acquiring a technic, it will be simply a question of time when the amateur disappears entirely….” That wasn’t a concern about Auto-Tune. That was renowned composer and band leader John Philip Souza in 1906, troubled by the player piano. Different gadget, same prophecy.

But Souza was wrong. In the years after his warning that player pianos would diminish the public’s interest in learning, the opposite occurred. According to a 1915 article in Music Quarterly entitled “The Occupation of the Musician in the United States,” census data revealed that between 1890 and 1910, the number of piano teachers in the U.S. increased by over 25%. It was an increase of 1.2 piano teachers per thousand to 1.5 per thousand. Perhaps the player piano decreased the rate of growth, but certainly the desire to make music didn’t die; it adapted. Practice rarely disappears, it just sometimes migrates.

That’s the pattern. The microphone changed the frontier from lung power to mic craft. Drum machines spread precision from wrists to arrangement. Sampling expanded creativity from takes to crate-digging and taste. Auto-Tune, used as an instrument instead of spackle, prized design and studio judgment. The practice didn’t vanish, it just morphed and moved.

Why then, do we get obituaries each time? Part of it is that these “practice panics” aren’t just about sound, they’re also about status. They can be a contest in who defines “real.” Norm guardians such as unions, established taste makers, conservatories, critics, and fans police the boundaries of “authentic” practice. If legitimacy has been long signaled by a specific kind of labor, a tool that reduces that labor can look like cultural vandalism. Thus, these prophetic proclamations of future despair can sound noble, cloaked in virtue (“for the craft”), but they may be an effort to protect yesterday’s pecking orders.

This is not to say that concerns are simply cynicism. We all build our identities around the techniques we’ve developed through blood, sweat, and tears. A new tool can rightly feel like an assault on meaning. But history shows us that though difficult to navigate, practice adapts and the tent gets bigger.

As the world around us continues to evolve quickly, it’s important that we keep the target in sight and separate the ends from the means. The end is expression, or in other fields it can be preserving resources, improving health, or something else; the means are the tools, and they can change without the sky falling. Perhaps it’s a question of scrutinizing the conduct instead of regulating the capability. We didn’t outlaw microphones because crooning scandalized 1928, and we shouldn’t bury pitch correction because 2009 felt overscrubbed.

“Real” lives in the listener’s gut, not in the checklist of chores that deliver it. Even Auto-Tune can be a new grammar, a new way to sculpt the soundwaves to create an authentic experience. So, the debate shouldn’t be about destroying the tool, it should be about how best to teach and to learn the craft where it now lives.

Innovation keeps relocating the work. Artists keep chasing it because that’s where the meaning is, that’s where there’s a chance to land a song as true because it enriches someone’s life.